⏱ A longer now

Time is probably one of the most overlooked factors when thinking, designing and planning for the built environment. How to change this? Issue #21

Hello everyone!

Happy to see you back here after this short break.

In today’s issue, we’ll discuss the importance of time, long time and what we can do in our practices to improve our understanding of it.

This issue is 100% inspired by my current reading of Flourish: Design Paradigms for Our Planetary Emergency, a fantastic and refreshing book by Singapore-based urbanist Sarah Ichioka and London-based architect Michael Pawlyn. Highly recommended!

In Chapter 3, titled “A longer now”, Ichioka and Pawlyn explore how we could rethink our relationship with time, and what it means for the way we design, plan and inhabit the built environment.

Across history, our perception of time has changed in many ways. On one hand, scientific discoveries have helped us realize our Earth’s long geological and climatic history. On the other hand, the rise of capitalism and globalization has accelerated our shortening of perspectives, and time has been increasingly commodified.

We are somehow lost between deep and shallow time.

Ichioka and Pawlyn brilliantly capture the challenges we are facing regarding our relationship with time. They have expanded their conversation through a podcast episode with Roman Krznaric, a public philosopher and author of the The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short Term World.

We live in the age of the tyranny of the now, driven by 24/7 news, the latest tweet, and the buy-now button. With such frenetic short-termism at the root of contemporary crises – from the threats of climate change to the lack of planning for a global pandemic – the call for long-term thinking grows every day. But what is it, has it ever worked, and can we even do it?

A lot of Krznaric’s ideas resonate quite well in the current context and I suggest we dive into this topic.

⏱ That’s our subject for this week: How to be a good ancestor and the role of time in planning for the built environment.

Don’t forget to subscribe to Cities in Mind, spread the newsletter around you or drop this issue into one of your company’s Slack channels !

⏳ The Invention of Time

As surprising as it might be, time is a recent invention and its perception is not as universal as we’d like to believe.

Before clocks were invented, people kept time using different instruments to observe the Sun’s meridian passing at noon. The pendulum clock was developed during the 17th century. In 1764, the chronometer was invented. Chronometers measured time accurately and became popular instruments during the 19th century.

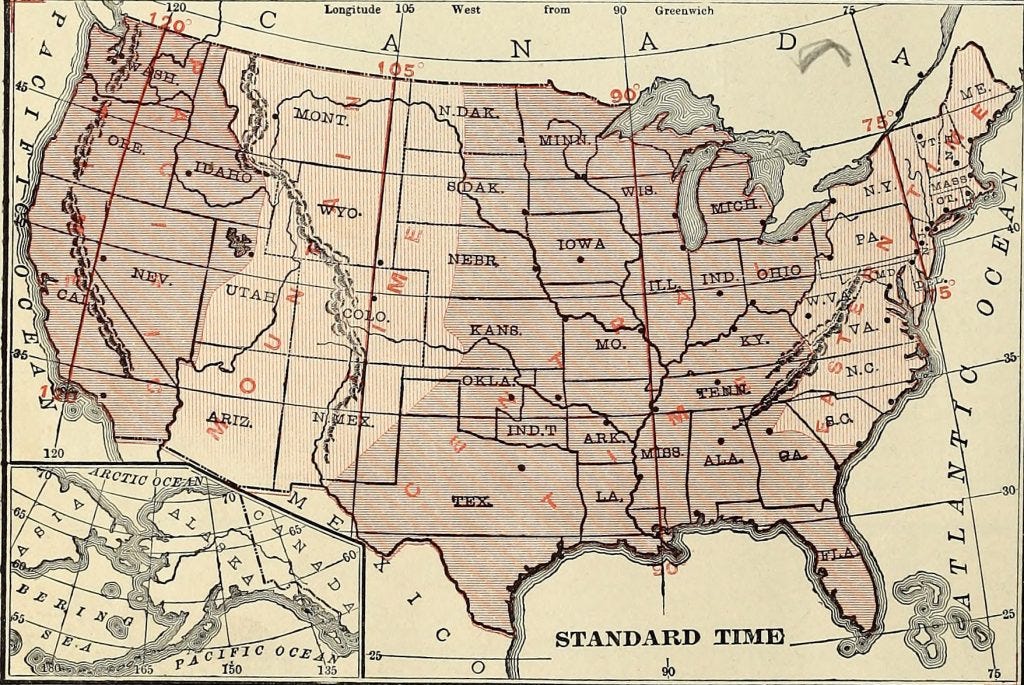

Even after the chronometer was invented, many towns and cities were still using clocks based on sunsets and sunrises. American railroads maintained many different time zones during the late 1800s. Each train station set its own clock making it difficult to coordinate train schedules while also confusing passengers. Operators of the railroad lines needed a new time plan that would offer a uniform train schedule for departures and arrivals, in order to boost travels and exchanges of goods. Four standard time zones for the continental United States were introduced in 1883.

The successful adoption of standard time in the United States set an example of how time zones could spread across the globe. By about 1900, almost all inhabited places on Earth had adopted a standard time zone.

Coordinated Universal Time, the primary 24-hour time standard based on highly precise atomic clocks, by which the world regulates time, was introduced in 1972.

Through these innovations, our sense of time radically shifted.

The idea of linear “clock time” has since become the norm, dividing time into units, to organize and control waged labour, steer production and facilitate commercial exchanges. Those units have become smaller and smaller. Financial trading now operates in microseconds. Clock time has also created a dominant story of progress: the future will continue to get endlessly better and we humans are able to escape natural laws and control time.

In indigenous cultures, the concept of time is much more fluid. Time is seen as a series of cycles: solar, lunar, tidal, with living ecosystems at the centre of seasonal phenomena. This translates into a different appreciation of time and space, revolving around the idea of “legacy mindset”, meaning long-term care of a place over time, for future generations.

In the West and in most globalized societies, the shortening of our timescales of thinking has made us disconnected from an ecological sense of place. We ignore the natural rhythms of life and we tend to forget what kind of natural assets existed in the recent past.

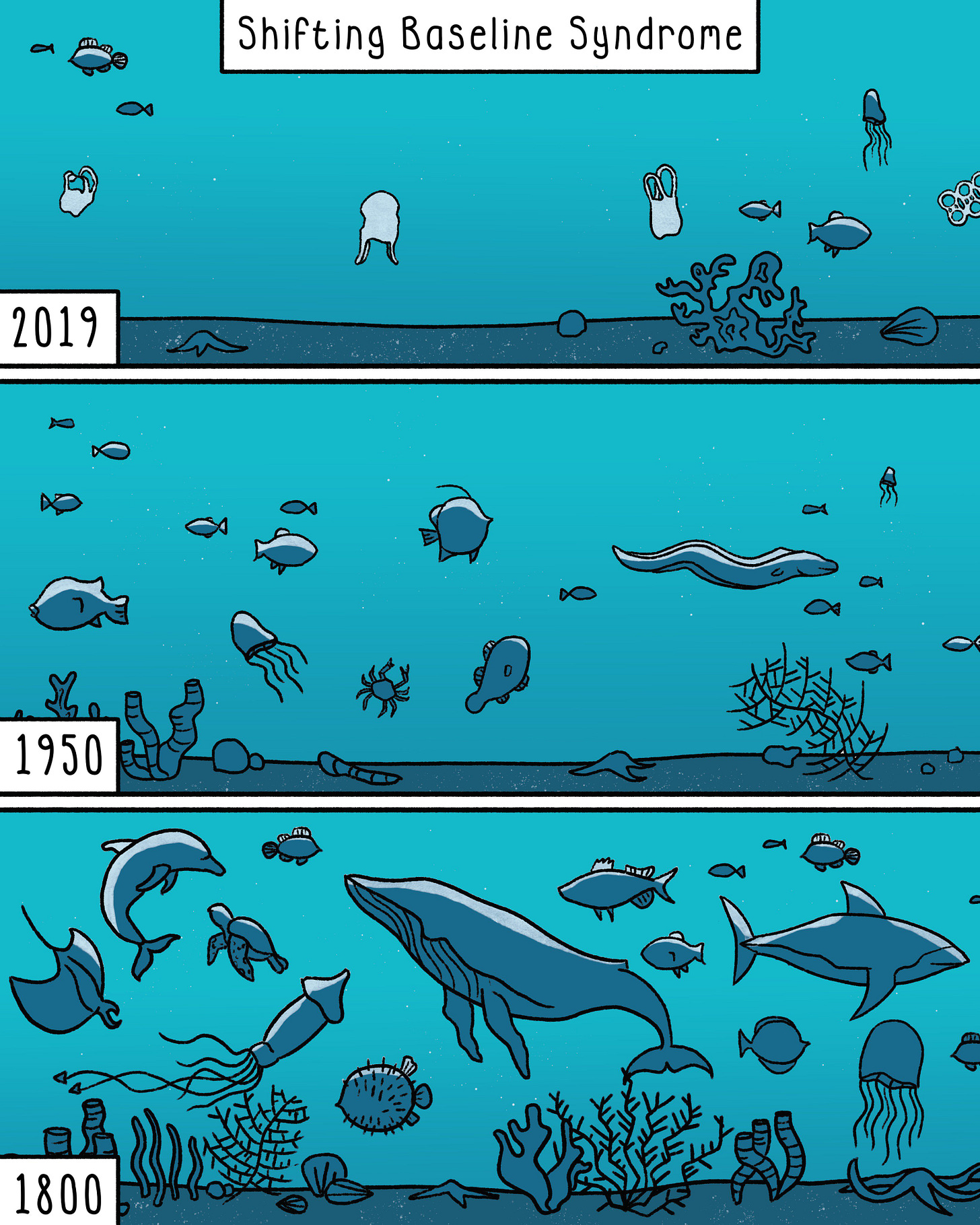

The concept of “shifting baseline syndrome” encapsulates this idea. First introduced by landscape architect Ian McHarg's in his 1969 manifesto Design With Nature , it was extended by marine biologist Daniel Pauly.

Pauly developed the concept in reference to fisheries management where fisheries scientists sometimes fail to identify the correct "baseline" population size (how abundant a fish species population was before human exploitation) and thus work with a shifted baseline. They end up trying to sustain a resource that had already been massively depleted because they’ve lost track of historical records and are working with the wrong baseline.

In addition, the contraction of time has made us dependent on technology for quick fixes and short-term “progress”.

In the Flourish book, Ichioka and Pawlyn take the example of large-scale visions such as the “Masterplanet” designed by Bjarke Ingels Group, a masterplan for the Earth to "prove that a sustainable human presence on planet Earth is attainable with existing technologies". Such ventures show our obsession with a particular idea of progress, as well as our faith in technology to solve our problems, if possible in a fast manner.

As you can see, we have a problem with time. And it’s time to fix it.

⛪️ Cathedral Thinking

Obsession for rapid changes, technological progress and fast-development cycles makes us unable to think long term. But things are changing.

Cathedral thinking, as explained by medievalist Jonathan Thompson (check his TED Talk), conveys the idea that one generation creates the foundations for something to be continued by the next generation. And so on.

In the Middle Ages, the architects and builders of a cathedral would enter into the project knowing that they would not live to see it completed. It was not unusual for cathedrals to require 200 years or more for completion. The generation that broke ground and laid the foundations would pass away, leaving their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to continue the work.

Cathedral thinking takes the long view. It means pursuing an ambitious goal or idea that might require several generations to complete. It means labouring in the present in service of future glory. It’s a mentality that allowed humans to achieve some of the greatest, most spectacular projects in history.

Cathedral thinking is still very much alive today and is making a comeback since the pandemic.

Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia (designed by the late Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí) is under construction since 1882 and anticipated to be completed in 2026, on the centenary of Gaudí’s death (or a bit later). The best current example of cathedral thinking.

At a different scale, bioregionalism is a movement that has been growing for more than four decades and which seeks to reconcile us with nature. By using natural features such as mountain ranges and rivers as the basis for political and cultural units, bioregionalism promotes systems change, in both time and space.

Probably one of the best documented bioregions in the world, Cascadia is a territory which ranges from Northern California to British Columbia in Canada (with also some portions of Alaska), including the entire watershed of the Columbia River.

Cathedral thinking in central in the Cascadian movement as it seeks to further local autonomy, empower individuals and communities to better represent their own needs, create sustainable local economies and plan for the long-term stewardship of the natural environment.

Long-term thinking is also starting to make strides in cities around the world.

The city of Vancouver and the University of British Columbia’s Design Centre for Sustainability have launched a 100 Year Sustainability Vision. “Operating under the themes of liveability, sustainability and resilience, this 100-year plan looks at likely scenarios, challenges and opportunities in the coming decades, allowing the City to develop more forward thinking policy planning and to be a better, stronger advocate for regional, provincial and federal sustainability legislation.”

In Japan, the Future Design movement invites local residents to discuss and draw up plans for the towns and cities where they live. Participants begin by discussing issues from the perspective of a current resident. Then, they are given ceremonial yellow robes to wear and told to imagine themselves as residents from 2060.

They go on imagining how their decisions today will impact on the lives of future generations – especially their children or grandchildren – leading to a shift in their priorities and choices. Their “discount rate” (the tendency to disvalue what you could get in the future instead of what you can get now) diminishes: they start putting more weight on the welfare of future citizens.

Such citizen assemblies are now becoming more and more common and help foreground the idea of cathedral thinking. There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that such deliberative citizen-based gatherings have a greater capacity to take the long view than traditional politicians who are often caught in short-term cycles. The UK and France’s recent climate citizens assemblies have proven to be interesting approaches to revive the democratic debate and foster long-term thinking, in the face of global challenges such as climate change or biodiversity loss.

How could we accelerate this shift towards longer-term ways of thinking? Can we move away from “time is money” to embrace “time is life”?

In the Flourish book, Ichioka and Pawlyn remind us that it will be a long journey and that we need to cultivate all the small efforts possible to help us shape a “longer now”.

What it means to be a good ancestor now is to view history critically, to rethink prevailing ideas about time and “progress”, and to collaborate with greater commitment and urgency than we have ever done before.

🧐 Some resources to dig deeper

The Flourish podcast episode on Long Time (a must-listen!) with public philosopher Roman Krznaric.

A media About Taking Time. Time is the greatest commodity we have, what do we do with it? This site offers a collection of essays, thoughts and writings on time.

The story behind the Doomsday Clock, a clock that monitors our time left before things get really serious. The clock started running in 1947, two years after the United States dropped nuclear bombs on Japan. It’s not literally a clock, more like a piece of art and maybe one of the most fascinating ones.

Our podcast episode on Futures Thinking with Singapore’s top futurist Cheryl Chung, at the NUS-Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. One of the most listened so far, where we discuss the importance of foresight to make cities such as Singapore more resilient.

The Ministry for the Future, by sci-fi genius Kim Stanley Robinson, one of the best books I have read in 2021, telling the story of a new climate-crisis international body “charged with defending all living creatures present and future who cannot speak for themselves”, dubbed the Ministry for the Future.

That’s it for today. I hope you’ve enjoyed this contribution. As usual, a small 💚 at the bottom of this page goes a long way.

Thanks for your support and see you next week. In my next post, I’ll share the results of the little survey I have run for the last couple of weeks. If you want to share your views on the newsletter, click on the button !