🇮🇩 Nusantara, Asia's new capital

Indonesia is moving its capital to East Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo. A bold decision that stirs controversy. Progress or folly? Issue #23

Hello everyone,

Something big is coming up in Southeast Asia. If you’re living in the region, you definitely know what it is. And even if you’re not, you’ve still probably heard of it.

Indonesia, the 4th most populous country in the world, is moving its capital to East Kalimantan, a province on the island of Borneo. The move is in part to relieve pressure on traffic-clogged Jakarta, which is sinking, polluted and crowded. The new capital city is also a way of symbolically rebalancing government operations, which are seen as too Java-centric.

This vision was announced by President Joko Widodo (Jokowi as everybody calls him) in 2019 and construction was supposed to start in 2020. Following COVID-19, everything was put on hold and planning resumed in 2021. In January 2022, the Indonesian parliament approved a bill to relocate the capital and it was subsequently announced that the new city would be named Nusantara (meaning “archipelago” in Indonesian). Around 1.5 million civil servants could be relocated to Nusantara, which will cover 2,560 km2, about twice the area of New York City.

“The new capital city is not merely a move of government offices. The main goal is to build a smart city - a new city that is competitive at the global level -, to build a new locomotive for the transformation of our country, towards an innovation and technology-based Indonesia with a green economy. This is where we will start.” announced President Jokowi during a speech in Bandung on 17th of January 2022.

As you can imagine, this project is stirring a lot of controversy. It will be developed in one of the most biodiversity-rich regions of the world, involve massive construction and infrastructure development, and drastically change the economic geography of Indonesia. Meanwhile, Jakarta which is poised to remain the economic centre of the country will still face the same challenges: overcrowding, land subsidence, pollution, regular floods.

On many aspects, this project leaves people skeptical. Notwithstanding the critics, let’s try to unpack its premises, implications and future challenges, as the whole endeavour is likely to go ahead.

🇮🇩 Nusantara, Asia’s new capital That’s our topic for this week.

Don’t forget to subscribe to Cities in Mind, spread the newsletter around you or drop this issue into one of your company’s Slack channels !

Cities from scratch

Moving a capital city is nothing unheard-of. Across history, developed and emerging countries have moved their capitals to new purpose-built areas, including the United States, Australia or Brazil. Closer to Indonesia, Malaysia has moved its government operations to Putrajaya in 1999 in order to release pressure on Kuala Lumpur while Myanmar did the same with Naypyidaw in 2005.

President Jokowi proposed the new capital in April 2019 and later that year picked the site in East Kalimantan province. The main motivations stated at the time were:

Moving the capital closer to the nation’s geographic centre

Spurring economic growth in the archipelago’s east (which is among the least developed parts of the country)

Easing Jakarta’s burden

Releasing pressure on Java

Jokowi is not the first Indonesian president attempting to move the capital. Plans to do so date back to the 1950s under Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno. Since then, other leaders including Suharto and Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Indonesia’s second and sixth presidents, have mooted plans only to abandon them in the face of insurmountable logistical problems.

The aspirations to move the capital can only be understood when looking at the dire challenges facing overcrowded Jakarta. Sprawling endlessly, the Jakarta metropolitan area is Southeast Asia’s most populous megacity, home to more than 31 million people, plagued with traffic jams and pollution, and notoriously sinking because of land subsidence. A 2020 flood killed more than 60 people and displaced more than 60,000. Without aggressive (or even, heroic?) efforts to limit the sinking, 25% of the capital area will be submerged by 2050.

Java as a whole is suffering from overcrowding. On an island roughly as big as England (129,904 km2), Java welcomes 147.7 million people. As the business, academic, and cultural hub of Indonesia, the island attracts millions of non-Javanese people to its cities, further pressuring conurbations such as Jakarta, Bandung or Surabaya.

Literally, a sustainability time bomb.

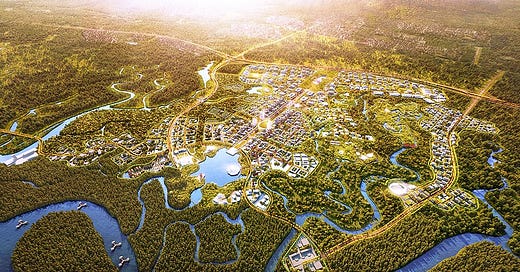

In response to the challenges facing Jakarta and Java, urban designers are envisioning an environmental utopia for Nusantara. All residents will be within a 10-minute walk of green recreational spaces. Every high-rise building will utilize 100% eco-friendly construction and be energy efficient. Of trips taken within the city, 80% will be by public transport or on foot or bicycle.

“Nusantara presents an opportunity to build a model city that is respectful of the environment” says Sibarani Sofian, Founder and Director of Urban+, the firm that won the competition for the design of Nusantara’s public government core.

An ambitious programme that stems from Indonesia’s plans to become a leader in sustainable energy transition (a core part of Indonesia’s current G20 presidency). Even if Indonesia’s renewable energy sector currently only provides 11.5% of national energy.

In that sense, Nusantara is part of a historical tradition behind planned cities, inspired by Keynesianism principles, where the central government intervenes and develops a vision to spur economic development, facilitated by top-down planning instruments and policies.

After all, Indonesia heads for economic superpower status. Although it is the world’s 4th most populous country, the 14th largest by area, filled with natural resources, the country keeps a remarkably low profile on the world stage.

This is about to change. And by 2050, Indonesia is poised to become the 4th largest economy. For many, it is time to show the world what the country is capable of.

But as much as the project is about asserting the power of the Indonesian State, there are other factors that turn this endeavour into a more neoliberal venture, with potential dramatic impacts on the environment.

Planning for profit

The construction of the new capital Nusantara will be done in three stages. The first phase, comprising the palace’s construction and basic infrastructures such as roads and housing, is slated for completion by 2024. The final stage of Nusantara’s construction is targeted to be completed by 2045.

About one-fifth of the $32 billion price tag is to be covered by the government budget, with state-owned enterprises and other private sector companies contributing the rest.

Other countries and firms are taking notice. And President Jokowi has been active travelling to secure budget for this new endeavour. With ups and downs.

On one hand, billion worth of commitments will come from Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia. On the other hand, Japan’s SoftBank, while initially committed to support the project, has recently pulled out.

But more interestingly, the “China factor” behind Nusantara will offer a catchy subplot, even if it is easy to exaggerate that dimension.

China is already backing a cement plant in the vicinity of the planned capital, which will likely be instrumental in the construction of Nusantara. The plant will employ 13,000 people and be capable of producing 8 million tons of cement per year.

China is also involved in the construction of the Indonesian Industrial Park (KIPI), a planned green industrial area in Bulungan Regency, North Kalimantan. In December 2021, President Jokowi stated that KIPI is expected to become the largest centre of green industry in the world (whatever “green industry” means). This 30,000-hectare project is projected to ultimately attract some $13 billion in investment.

The selection of Kalimantan as the site for Nusantara may facilitate increased Chinese investment on the island of Borneo.

The influence of China is a sensitive topic in Indonesia and might be politically instrumentalized in the future to undermine the whole project. Yet, it is one manifestation of the importance of neoliberal policies when it comes to building planned cities.

Beyond its Keynesian features, Nusantara is strongly influenced by urban neoliberalism, centring on market mechanisms, foreign investments, public-private partnerships, commodification of real estate assets for capital accumulation.

The triptych “People-Planet-Profit” often appears on Nusantara’s presentation decks and webinars.

There’s an interesting comparison to be made with “Sisi-City”, Egypt’s new capital, currently under construction. A huge “New Administrative Capital” is being built, approximately 45km to the east of Cairo, on a swath of desert equal to the size of Singapore. It is expected to house embassies, government agencies, the parliament, 30 ministries, a presidential compound and some 6.5 million people when completed.

The New Administrative Capital is expected to cost about $40 billion. 51% of the Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD), the company which oversees the project, is owned by the Egyptian military and the remaining 49 % by the Ministry of Housing. Despite some foreign investments from the UAE, the military has an enormous role in funding the project and its tentacles stretch across the economy, from steel, cement to agriculture, fisheries, energy, healthcare, food and beverages.

The project is so large and so lucrative that it will also create opportunities for the private sector. One of Egypt’s biggest construction companies, Talaat Mustafa Group, has laid the foundations for “Noor City”, a “smart city project” within the New Administrative Capital.

It’s another manifestation of neoliberal modes of urban production, mixing international financial interests with public (and in the case of Sisi-City, military) interests. Sky’s the limit when it comes to investing in such gigantic projects which are conceived as engines of growth and magnets for foreign investors.

Save the forest

Planners are often skeptical when it comes to building cities from scratch and usually for good reasons.

The impacts of Nusantara on Borneo’s ecology and indigenous culture could be substantial.

An island the size of California, Borneo, which is divided between Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia, features enormous natural resources and carbon sinks, such as coastal mangroves, forests, swamps, and mountains, hosting numerous endemic and rare species.

The government has highlighted that Nusantara will be built on a previously cleared site and will rely on existing highways, power lines, and other infrastructure. The cities of Samarinda and Balikpapan, close to the future site of Nusantara, have already their airports which could be used to serve the new capital (even if Nusantara might get its own airport).

The location for the new capital also lies inland, allowing for shoreline mangrove preservation and restoration. River valleys will also be protected and remain as important green & blue corridors, as visible in Urban+ ’s design.

But concerns are that Nusantara will likely trigger sprawl beyond the city limits and development across Borneo. Spurring economic growth is, after all, one of the goals of the project.

By studying the increase in nighttime lights associated with 12 previously relocated capitals, including Brasilia and Naypyidaw, a team of researchers led by ecologist Alex Lechner of Monash University, Indonesia, found that they burgeoned initially, then grew more slowly.

“Our assessment suggests that it is likely that [Nusantara’s] direct footprint could grow rapidly, expanding over 10 kms from its core in less than two decades and over 30 kms before mid-century,” the team reported in 2020 in the scientific journal Land.

Nusantara will impact the economic geography of Kalimantan and Borneo as a whole, one of the world’s richest biodiversity hotspot. Kalimantan has already lost about 30% of its original forest cover to land clearing and fires since 1973. Endemic species such as the Bornean orang-utan and the proboscis monkey are increasingly endangered.

President Jokowi has recently announced that Nusantara will be a “Forest City” and that the area, which is currently characterized by monoculture and industrial plants, will be turned into a forest of endemic plants. He recently planted trees coming from 34 provinces across Indonesia at Nusantara’s ground zero point.

For many, it resonates as corporate communication. There are still laments and conflicts around land acquisition, and the status of local indigenous communities remains unclear.

Across the Indonesian archipelago, indigenous and rural communities have been fighting to reclaim their ancestral lands from mining and logging concessions, following a landmark 2013 court ruling to lift state control over customary forests.

Jokowi has vowed to return 12.7 million hectares of such land to indigenous people, but progress has been slow with conflicting claims and multiple maps. More than 20 communities comprising thousands of indigenous people risk being uprooted from their land to make way for Nusantara. And with them local wisdom about the forest and its fragile ecosystems might forever disappear.

And last but not least, what will happen for Jakarta is uncertain. Jakarta is poised to remain the economic centre of Indonesia and still has to take on its social and environmental issues. So far, no real plans have emerged to deal with the future of Indonesia’s current capital city or Java as a whole.

I guess the priorities are somewhere else.

What did we learn today?

Indonesia is moving its capital to the East Kalimantan province by phases from 2024 till 2045. The new planned city, called Nusantara (“archipelago” in Indonesian), will gradually welcome 1.5 million civil servants, relocated from Jakarta.

While inspired by Keynesian principles of state intervention, Nusantara is ultimately influenced by urban neoliberalism. The attraction of foreign investments is instrumental in the making of the new capital.

Nusantara will likely trigger sprawl beyond the city limits and development across Borneo, endangering biodiversity and local indigenous cultures already present there.

Jakarta (and Java as a whole) will remain the economic centre of Indonesia with no clear plans as how to tackle its pressing issues, such as land subsidence, pollution, overcrowding and urban congestion.

🧐 Some resources to dig deeper

Indonesia’s utopian new capital may not be as green as it looks Indonesia has yet to start building its new capital, Nusantara, but a slick website shows what the country has in mind. A video shows people strolling on boardwalks through lush greenery, housing perched on the shores of an idyllic lake, stunningly modernistic buildings, elevated mass transit lines, and bicycles on tree-lined boulevards.

An internal colonial project in disguise Indonesia’s decision to move its capital from Jakarta to a new city in East Kalimantan excluded local and indigenous communities from the planning process. Now, Nusantara threatens their land, culture and livelihoods.

Jakarta’s recent progresses to tackle congestion by the recently launched urban-related newsletter Infinite Block and written by the brilliant Max Kim - How one of the most-congested/polluted cities in the world is turning things around.

Indonesia Etc. A great book that helped me to understand the complexity and diversity of Indonesia’s culture when I was conducting research work there. How do you make 260 million people on 6,000 islands feel like they are all the same nation? Author and researcher Elizabeth Pisani takes a look at post-independence Indonesia.

From Sisi-City, Egypt to Neom, Saudi Arabia, why some global South countries keep building new planned cities? (in French) Planned cities are emerging in many countries, displaying high ecological ambitions but only to aggravate urban sprawl. Are planned cities a winning economic bet?

That’s it for today. I hope yo enjoyed this contribution. As usual, a small 💚 at the bottom of this page goes a long way.

Thanks for your support and see you next week.

Fascinating. Thanks Fabien

Great piece! I think the funding aspect is something that a lot of "cities from scratch" tend to overlook or put off as long as they can, so very interesting to hear the actual steps the government is taking, including private and international funds. Thanks for sharing