Platform Urbanism in Asia - Issue #9

Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger. How Asia's Super-Apps are reshaping city life and increasing their influence on the built environment.

📱 This week, we’ll start exploring the rise of “Platform Urbanism” in Asian cities. I say “start” because there’s a lot to cover and unpack. Stay tuned for more posts on this topic.

My inspiration for this issue largely draws from a recent article by Rob Goodspeed, Associate Professor or Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Michigan, Are We in the Era of Platform Urbanism?

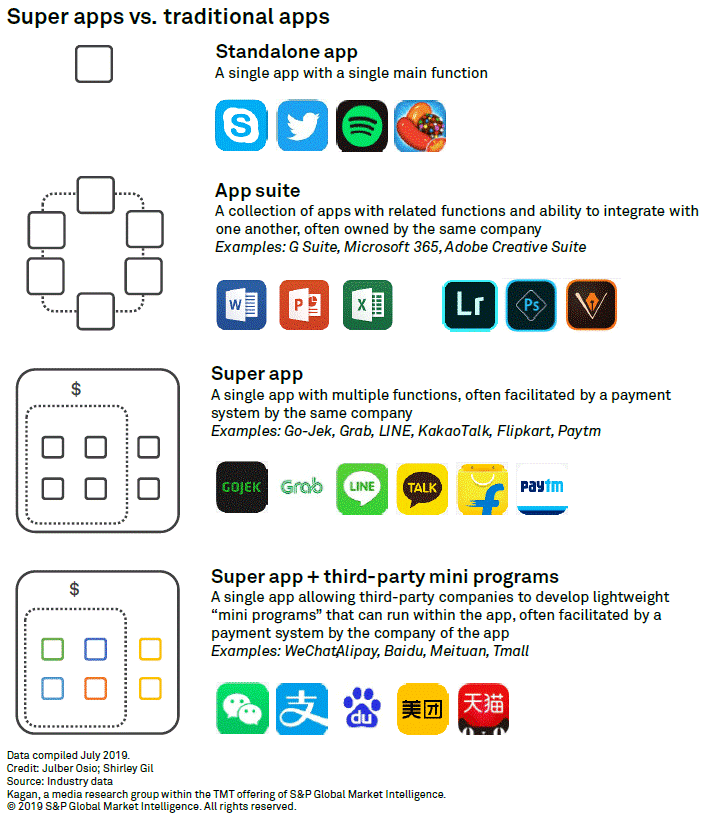

A platform is basically a specific use of technology that facilitate social and economic activities. “Instead of simply creating stand-alone software products, platforms [create] the spaces that [allow] others to innovate as well,” according to Sarah Barns, an expert on the topic and author of Platform Urbanism: Negotiating Platform Ecosystems in Connected Cities.

“Through the use of technology to cultivate a two-sided market, firms using a platform strategy seek to create a monopoly within a particular economic sector, but one which also supports an ecosystem of others who benefit from the platform, such as app developers and users. By serving as an intermediary, the platform captures profits, as well as obtaining data that can be used to develop further products and services which serve as sources of further growth.”

Rob Goodspeed, Associate Professor or Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Michigan

You’re probably familiar with the main Western protagonists of the “platform economy”: Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Amazon, Deliveroo.. They all have disrupted large chunks of our economies (the “Uberisation of Everything”) and continue to shape our lifestyles and preferences.

You might also have heard about their Asian counterparts: Grab, GoJek in Southeast Asia; Alibaba’s Alipay, Meituan (delivery), WeChat in China ; Kakao in South Korea, Line in Japan... Asia is the land of “Super-Apps”, a common shape that platforms take in the region, defined as “all-in-one experience portals”, giving access a wide range of virtual products and services.

Like anywhere else, platforms in Asia are moving targets. Their impacts on the built environment are largely undocumented and how much they will influence the future of cities remains unclear.

How much are super-apps shaping lifestyles in urban Asia? Are urban management and governance the next frontiers of platformization? Will Asian cities move towards Platform Urbanism? And what does Platform Urbanism mean anyway 🤔 ?

🌏 Meet your Asian Tech Giants

Tracing back the roots of platform economics in the region invariably leads to China.

China has indeed set the playbook for many super-apps in the region. Not that China has necessarily invented super-apps but the country has gone the farthest in integrating them into its economy and into people’s daily lives.

China has pioneered the development of “mini-programs”, i.e. little downloadable apps developed by third parties that run inside another larger super-app, like for example WeChat. Integral to the success of WeChat or Alipay's mini-programs are the native mobile payments systems WeChat Pay and Alipay.

Mini-programs + integrated payment systems, that’s the magic combination that explains the rapid uptake of such applications in the region.

Indonesia's GoJek and Singapore's Grab — the biggest super-apps in Southeast Asia — followed this model of developing their own services and packaging them into one single app. Both of them initially started as ride-hailing apps and then expanded their own branded services through their mobile payments systems, Go-Pay and GrabPay.

Grab, which is one of the most valuable start-ups in Southeast Asia and which is set for a USD40 billion IPO, is quickly evolving into a full-service suite of financial products, complimenting its suite of food delivery and e-commerce services.

On the other end, GoJek is in talk to merge with Tokopedia, an Amazon-like company connecting merchants with buyers in Indonesia, a country of 270 million people on which GoJek focuses its efforts (rather than regionally expanding like Grab).

The “mobile-first” culture of many Asia-Pacific countries, coupled with less concerns about incorporating multiple services (and a lot of personal data) into one single app, have paved the way for the creation of mobile giants, from mobility, commerce, lifestyles and now financial services.

🤖 Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger

Asia shows how super-apps are having major implications on local economies, urban lifestyles, management and governance. Those implications are not easy to distil in practical terms but let’s try to flesh out some key dimensions.

Harder

As we’ve seen, the deployment of these super-apps in the region has been rapid and impressive. COVID-19 has accelerated the push towards e-commerce, e-payments and food delivery in the region and there is little doubt that these platforms will continue shaping the lifestyles and preferences of Asian urbanites.

Western countries might experience a gradual transition of existing platforms into super-apps but in Asia, fierce competition has led to a speed-up in super-app deployment and adoption.

In Southeast Asia, the battle of super-apps is boosting the digitalisation of large economic sectors and some super-apps are even flirting with profitability (something most platforms are struggling with). After a decade, GoJek says it’s generating positive gross margins.

Better

The COVID-19 pandemic was also a big test for these platforms and most of them have emerged as indispensable partners to revive local businesses, mostly F&Bs, and to rebuild the livelihoods of small merchants and workers impacted by the crisis.

During the peak of the pandemic in 2020, Grab launched a new application called GrabMerchant, a one-stop service platform for SMEs, mostly in the F&B business, to digitally manage their operations, offers and visibility. Similarly, GoJek Indonesia introduced services to help facilitate SMEs' digitalization, such as GoBiz, that allows small businesses to manage their company online and access new customers.

That being said, Grab and GoJek are not social enterprises and they are facing their fair shares of backlash.

GoJek is for example criticised for over-using gamification techniques and complex algorithms that confuse its drivers. Indonesian ride-hailing giant GoJek uses a complex system of reward and punishment to motivate its drivers, but its contractors say that it is exploitative. It is also currently facing a series of strikes from its drivers who protest its plan to slash incentive fees After GoJek’s merger, are Indonesian delivery riders getting a worse deal?

Faster

Asia’s super-apps have enabled the rise of “quick-commerce”, the idea of bringing small quantities of goods to customers almost instantly, whenever and wherever they need them. A topic we discussed in our podcast series with Singapore’s Managing Director of Food Panda, one of Southeast Asia’s largest food delivery platforms Episode 04 - The Rise of Q-Commerce in Asian Cities

The Instant City, powered by these super-apps, offers a questionable horizon, fuelling our propensity for lazy and sedentary lifestyles.

“The speedy delivery platforms quickly move on. Not wanting to rely on getting food from a restaurant at busy times, they are setting up their own ‘cloud kitchens’ in edge-of-town warehouses. Not wanting to rely on picking items from local shops, they are creating their own ‘dark-stores’ or ‘D-marts’ stocked with their own brands. Not wanting to rely on people to meet the punishing delivery schedule, they are investing heavily in developing delivery drones.”

Peter Madden, Professor of Practice in City Futures at Cardiff University

Stronger

Finally, the gradual integration of financial services into these super-apps has accelerated their gigantic takeover on people’s daily lives. Financial services present a rich and untapped market of opportunity for Southeast Asia’s super-apps to dive into, as over 50% of the region remains unbanked today.

Some platforms have also diversified into urban and traffic management. The most prominent example is Alibaba’s City Brain programme which began in 2016 in Hangzhou, China (home to Alibaba’s HQ) as an AI real-time solution to monitor traffic, using data from the transportation bureau, public transportation systems and surveillance cameras.

Overlapping with other high profile tech initiatives, such as China’s social credit system, City Brain is emblematic of China’s efforts to promote its own model of smart city. The programme has expanded to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in 2018.

But interestingly, those expansions and diversifications are not a walk in the park. China recently cracked down on Alibaba and other tech firms, accusing them of offering unsecured loans and financial products to members of the public and pushing them to borrow more money than they need or can afford to pay back. Alibaba’s Founder Jack Ma’s empire is also slowly being dismantled by the Chinese government, the country’s richest man being accused of “abusing its market dominance”. Monopolistic tech giants also rise and fall, it seems.

🆚 Technologists vs Urbanists

Even if it’s still in its infancy, “Platform Urbanism” is an interesting concept as it captures the challenges of urban life today, where various platforms play an outsized role in people’s behaviours and become central in how they navigate, consume, and live in cities.

It suggests to analyse how platforms and super-apps work, understand the new services they deliver, analyse their impacts and potential negative externalities (pollution, traffic congestion, over-consumption, sedentary lifestyles..) and design an action framework where cities are not any more mere observers but become active players.

The concept has yet to be further defined and tested. Today it sounds a bit like an oxymoron, considering the divergences between technologists (high financial risk tolerance, experimentation-oriented, short-term goals) and urbanists (low financial risk tolerance, planning-driven, long-term thinking), something we discussed in one of our recent posts.

Central to these divergences is the response to the “Commons” - i.e. the free-to-use resources and infrastructures that underpin the deployment of such solutions, namely roads, streets, curbs, public spaces but also, to a certain extent, digital information about a city’s infrastructure, networks.

Technologists, platforms and super-apps are tapping on them freely to develop their businesses. Urbanists are trying to regulate and protect them.

Overcoming these divergences is easier said than done but let me suggest 6 priorities for a Platform Urbanism agenda.

Balance Public & Private Interests - platforms create products and services with important urban implications, which need to be rebalanced by targeted policies.

Understand the Models - economic models that powered current platforms have far-reaching socio-economic consequences, on users, workers and businesses. Unpacking and understanding them is the first step.

Protect the Commons - free-to-use resources (physical or digital) being utilised by platforms are key assets. Their protection and regulation is central.

Keep the User in Mind - platforms respond to (and create) users’ needs. They are user-centric by design. As the value to users and customers takes centre stage, public action needs to adapt and balance systems vs user thinking.

Adopt “Ecosystem Thinking” - platforms are part of larger and dynamic ecosystems (mobility, food, logistics, banking) where actors are interdependent, sharing data, collaborating or competing.

Govern Differently - There is a need to combine regulation and facilitation. Platforms are moving targets and call for new action models (and tools) to equip cities in their response to changing landscapes.

With their tradition of state interventionism, Asian countries might be best placed to outsmart the rise of the super-apps and integrate them in their long-term economic and social development plans.

Will they succeed where the US and Europe are struggling?

📝 Read, listen, watch this week

The end of smart cities? Worldwide deployment of smart city projects is declining

Will Work-from-Home Work Forever? Another great podcast episode of Freakonomics Radio

Extract: “As of today, roughly 50 % of U.S. workers are still virtual; a year ago, that number was around 70 %. What will it be a year from now? No one really knows. Some predictions say that office work will eventually return to pre-pandemic levels. Other predictions say that office work has been broken forever, that too many workers have seen the light. One new research paper, based on survey data, estimates that 20 % of full work days will now be from home, versus just 5 % before the pandemic.”

China’s Concrete Jungles Make Room for Green Space A national push to build urban parks is transforming Chinese cities, as the country tries to improve the quality of daily life

The Space Between, written by my former colleague Andrew Stokols, exploring the interconnection of urban infrastructure and government strategies in urban China, taking the example of Xiong’an, a new city under construction about 100 km south of Beijing

Eminent Earth Scientist Johan Rockström on his latest Netflix Documentary Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet (go and watch it if you haven’t already) “We need bankers as well as activists… we have 10 years to cut emissions by half”

💡 And also

🎙 ICYMI our latest podcast episode with Think City about the future of Malaysia’s most innovative city, Penang Episode 08- Putting a mid-sized city on the map: the journey of Penang, Malaysia

That’s it for today. As usual, a small 🧡 at the bottom of the article goes a long way !

Thanks for your support and see you next week for a new podcast episode. Stay tuned!