The Battle of the Maps - Issue #10

How mapping information is becoming a crucial differentiator for ride-hailing companies and global tech platforms, in Asia and beyond.

This week, we’ll continue exploring the topic of “Platform Urbanism” and the many ways the platform economy influences our built (and digital) environment, especially in Asia.

Mapping is probably the most unknown battle behind the fierce competition of ride-hailing companies.

Without proper maps and cartography systems, ride-hailing companies cannot develop location-based products and services, manage their fleet of riders and delivery men, access their customers and provide real-time information for their end-users.

As geospatial giant Esri founder Jack Dangermond put it “Knowing where things are, and why, is essential to rational decision making”.

Is mapping the new frontier of platform urbanism? What can we learn from the recent incursions of ride-hailing companies in that space? How can new location intelligence services inform city decisions?

The New Cartographers

As ride-hailing champions, such as Grab and GoJek, expand in Southeast Asia, good road network data has become a highly sought-after resource.

Both companies rely heavily on accurate maps, for example to know where their drivers are and where they are going or to bring down the “rendez-vous distance”- the distance customers typically walk to get to their ride - an old problem that many of these companies are struggling with. The company which will manage to substantially reduce the “rendez-vous distance” will have a major competitive advantage.

Southeast Asia has been facing many challenges when it comes to high-quality road data, as urban landscapes change quickly and points of interest (POIs) transform over time.

To that end, both Grab and GoJek have been building up their own cartography capabilities.

"Staying up-to-date with fast-paced places like Jakarta will require a variety of inputs," says Nate Smith, Head of business, cartography at GoJek

"For example, many restaurants and businesses can move in less than a year, so accurate street view imagery and on-the-ground validation will be critical in keeping our maps updated”

Grab collects its own street view imagery. In November 2019, it opened an Innovation and Engineering Lab on the outskirts of Jakarta where dedicated staff develop mapping systems and explore new ideas, such as the use of drones to detect narrow streets and the creation of indoor maps for building complexes (another important issue in vertical and dense Asian cities).

Grab also taps on its riders to map the cities in which it operates, leveraging the power of crowdsourcing to identify missing places and roads. Grab’s drivers – who collectively traverse 320 million kilometres each day – are incentivised to support road network data collection and identify important Points of Interest.

Between October 2017 and January 2018 alone, Grab received 50,000 inputs from drivers across Southeast Asia - such as information about difficult-to-access pickup spots or potential better routes. In this way, Grab has discovered more than 750 km of undocumented road segments in Jakarta alone.

But collection of cartographic data requires significant investments of time, labor and money. And money is precious, given that investors currently focus on regional ride-hailing companies' profitability.

That’s why some of these companies are turning towards external partners, such as StreetCred, a U.S. mapping startup which has created a blockchain-based marketplace where users are rewarded for helping to collect road data. StreetCred organises city contests where volunteers map their city and are remunerated with bitcoin prizes (don’t get too excited, in the case of Jakarta’s contest in 2020, the weekly prize was around 0.08 bitcoin, split between the top 10 winners).

Maps are more than ever the power engine of the platform economy and the backbone of fast-growing super-apps, which have emerged from ride-hailing.

The “Digital Gentrification” of OpenStreetMap

In their quest to become mapping leaders, ride-hailing companies have joined other corporations in contributing to free and open mapping initiatives. Inside the ‘Wikipedia of Maps,’ Tensions Grow Over Corporate Influence.

You might be familiar with OpenStreetMap (OSM), also known as the Wikipedia of Maps, a collaborative project launched in 2004 to create a free editable map of the world. There are currently more than 5 million registered users, about 20% of whom have edited the map. Historically, OSM volunteers make edits that increase the representation of their communities or reflect humanitarian-minded interests. OSM has an humanitarian branch, called HOT (Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team) providing tremendous benefits for humanitarian aid, disaster responses and economic development.

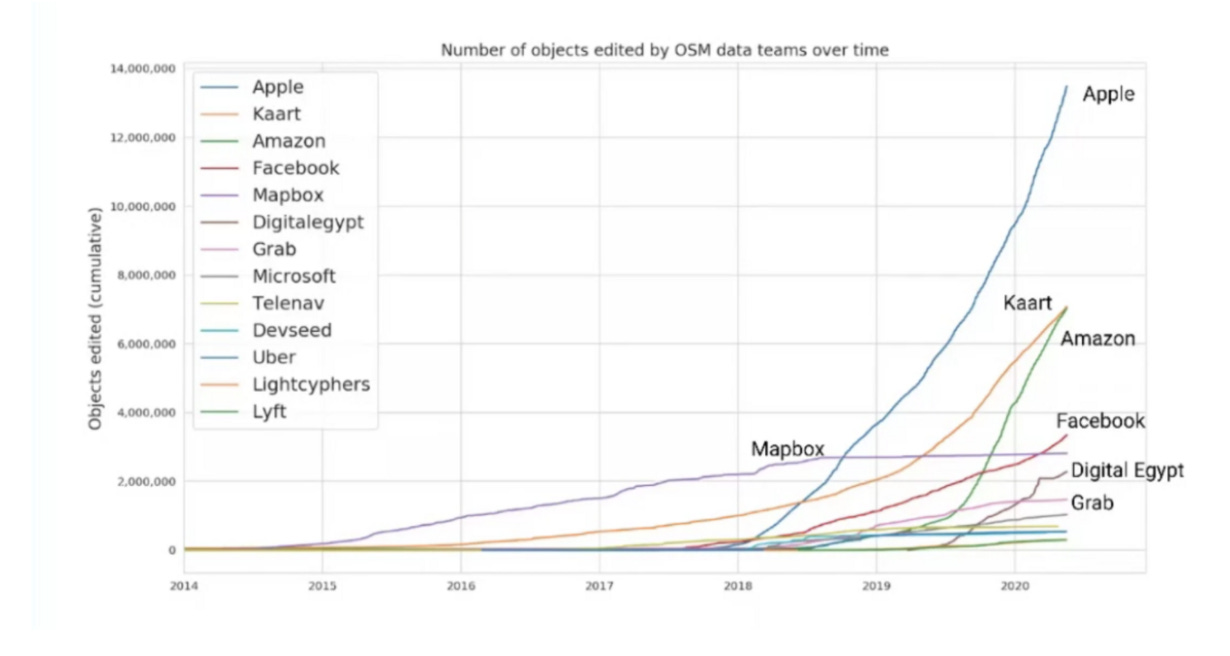

In a 2019 paper, a team of researchers from the University of Colorado, Boulder and the National University of Singapore have shown that large tech companies, such as Facebook, Apple, Microsoft were gaining a lot of prominence as editors of the map.

Since the costs of business subscriptions to Google Maps and other proprietary data sources have significantly grown over time, more tech companies (that provide location-based services) are turning to OSM as a free data source.

OSM offers a lot of advantages (first, it’s free) and private companies can also make changes directly, especially road data that is key for a lot of future product developments.

Apple, which uses OSM data as one of several sources for Apple Maps, is currently the most prolific corporate editor and was responsible for almost 80% of all edits to pre-existing roads in 2018. Amazon’s influence is also growing rapidly as its logistics team incorporates data from delivery drivers. In Asia, Grab is leading the charge, at rates quite limited compared to others.

The rise of corporate mappers has stirred some tensions with the longtime OSM editors. Information that corporations collect from their own sources is not always fed back into OSM and their priorities might be different from the rest of the community. It has led some OSM mappers to view corporate influence as a threat to the open-source project’s core values of data attribution and reciprocity.

Such issues could lead to what Jessical Lingel, a communications professor at the University of Pennsylvania, calls “digital gentrification” in which the push from corporations alters the spirit of community-driven crowdsourcing.

The problem is not new and many argue that a diversity of perspectives might not necessarily be negative. The combined efforts of corporate and volunteer editors could make OSM more powerful and accurate.

Dipto Sarkar, one of the researchers, concludes: “If the data quality increases and the community stagnates, OSM becomes something entirely different” “If both struggle because of these changes, OSM as a whole might die out.”

Location Intelligence as the New Frontier

The last battlefield I want to mention is related to the development of new location intelligence services. Mapping products is indeed becoming a crucial differentiator for global platform companies.

In the US, Coord, a spin-off of Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs, is busy mapping out US cities’s streets and building a massive database of their different regulations.

As the driverless revolution gives rise to more kinds of vehicles, new ways to use them and new behaviours, cities will need more complex regulations and fine-grained information about how to apply them at the very local level, down to each curb. Building a real-time mapping platform that tracks every AV’s movement in the city also offers to possibility to generate revenues from curb usage, parking time, drop-offs, pick-ups and so on.

That’s precisely what Coord wants to achieve.

Coord bets that cities will want to outsource the mapping, collation, dissemination of street regulations instead of building their own system. And in fact, many US cities have incomplete and inaccurate records of their own traffic rules and how they spatially translate to each street. So why not rely on Coord to do the job?

The risk is for municipalities to depend on Coord’s service in perpetuity and to loose the opportunity to own and control this vital road network data.

Back to Asia, new location intelligence services take different shapes. By building huge travel datasets, ride-hailing companies are able to advise cities on their urban mobility strategies.

Grab-Posisi is the first GPS trajectory dataset of Southeast Asia (data is collected from Grab drivers’ phones while in transit). The trajectory patterns from users GPS data are a valuable source of information for a wide range of urban applications, such as solving transportation problems, traffic prediction, and developing reasonable urban planning.

On top of this, Grab aims to leverage its AI capabilities and develop algorithms to improve precision and accuracy in mapping pick-up points and tracking moving vehicles. This is in line with the company’s efforts to become an “AI-Everywhere” company to solve Southeast Asia’s biggest urban problems.

Grab has launched in 2018 a partnership with the National University of Singapore, called the Grab-NUS AI Lab, to leverage data from the Grab platform to map out traffic patterns and identify ways to directly impact mobility and liveability in cities.

Using data analytics, the Grab-NUS AI Lab has identified the busiest routes in Singapore during peak hours. Such insights can inform the authorities to better serve the routes with more shared transport solutions, such as buses and trains, while Grab can increase and adapt its services.

That’s one step further towards ride-hailing becoming an indispensable piece of every city’s mobility strategy.

📝 Read, listen, watch this week

The Donut Effect of Covid-19 on Cities Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom has found that most of the people who left cities in the US during the pandemic moved to nearby suburbs, not distant Zoom towns.

America has eight parking spaces for every car. Here’s how cities are rethinking that land. Hint: tactical urbanism. A topic we will explore in our podcast episode next week.

Say bye to the Central Harbourfront Event Space in Hong Kong, probably the most expensive piece of land in the world currently for sell.

And because we talked about maps in this post: Mapping Nothing Many pandemic maps depict the macro-scale forces that produced the “Great Pause.” What’s harder to show are all the under-appreciated actors that are enabling our protected isolation, the pulsing activity powering the pause.

An AR app to visually delete buildings in Tokyo. Don’t want to see that ugly building complex anymore, just remove it!

💡 And also

🎙 ICYMI our latest podcast episode with Dr Perrine Hamel from the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore Episode 09- When Nature is the Solution: Cities in Green & Blue

That’s it for today. As usual, a small 🧡 (or even a comment) at the bottom of the article goes a long way !

Thanks for your support and see you next week for a new podcast episode. Stay tuned.