"Micromobility is urban mobility" - Issue #13

Horace Dediu from Micromobility Industries tells us why the mobility revolution in cities is here to stay.

Hello everyone!

This week’s missive will be quite short, as I am currently juggling with many different projects.

I’d like to share with you a video I recently watched: The 10 Micromobility Commandments by Horace Dediu 🛴 🚲

For those who don’t know him, Dediu is an American industry analyst and technology expert, founder of (among many other things) the Micromobility newsletter and podcast (I highly recommend this newsletter for those who want to get up to speed with urban mobility innovations). Dediu coined the term “micromobility” in 2017 to describe shared vehicles weighing less than 500 kg. Since then, there has not been a single day without a news article, report or analysis about how micromobility will transform cities.

The pandemic has accelerated this trend, with e-scooters, bicycles, e-bikes and other low-speed forms of urban transportation taking over city centres all over the world. But of course, the history of micromobility starts earlier.

In 1965, activists in Amsterdam implemented what is now considered the first bike sharing system in history. Known as Witte Fietsen ("white bikes"), the bottom-up initiative collected bicycles, painted them in white, and simply placed them on the streets for public use. The program was ultimately short-lived (free white bikes were quickly removed by the police) and it was only in the 2000s that large cities in England, France and Spain started to introduce citywide bike sharing systems that utilised magnetic strips and tracking technologies. Many other cities in North America and Asia followed.

But a new boom happened in 2016, when Chinese startup companies started to flood Beijing, Shanghai and other cities worldwide with fleets of free-floating colourful bicycles. This model did not last long and led to a lot of criticism of cash-burning tactics adopted by dockless bike sharing startups.

This article The rise and fall of Chinese bike-sharing startups gives precious insights about this period.

“Explanations of what exactly went wrong are still evolving, but it seems likely that the mind-boggling amounts of cash pumped into what wasn't essentially a "bike-sharing" model, but rather a rental business pepped up by a smartphone app, had something to do with it.”

Yet, this episode concretised the era of micromobility and since then all eyes are on cities adapting their mobility strategy to prepare for this new revolution.

Let’s hear some key insights from Dediu and why he thinks micromobility in cities is here to stay and thrive.

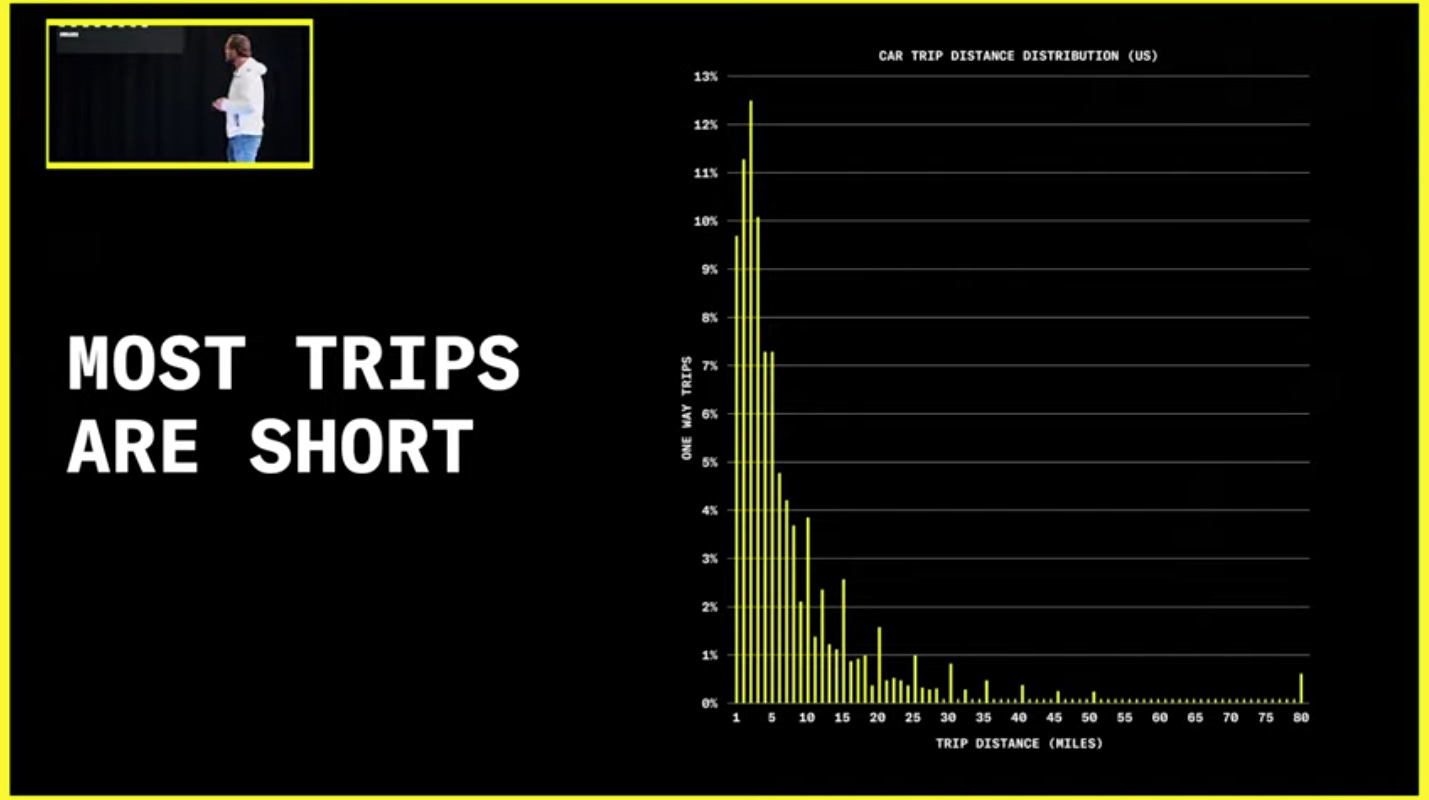

Most trips are short

That’s a fact. And yet that’s probably one of the most overlooked urban facts.

Dediu draws a comparison with the mobile industry, juxtaposing our car trips with our smartphone session lengths. Most of our smartphone session lengths are very short (70% are 0-2 mins), similar as our car trips, at least in the US.

There are huge opportunities to tap on that value, like there are huge opportunities to tap on our short screen activity time. By focusing on the “short”, Dediu says that we could distribute to other modes of transportation the value that cars currently capture, from bicycles to e-scooters to light vehicles, eventually leading to the removal of cars.

Same as the mobile revolution, the development of micromobility solutions will be exponential and will drive innovation for years to come.

Fruit Flies and Elephants

The small grows faster than the big.

Dediu draws another parallel between the personal computer era and today’s electric vehicles. When smartphones reached an affordable price point, they dramatically increased the size of the market and overpassed personal computers.

Micromobility will follow the same path. E-bikes, scooters and yet-to-be-invented personal mobility devices will similarly expand the market and overpass electric cars, which are still capturing most of the attention today.

Let a thousand flowers bloom, as they say.

Cities always win

Micromobility is urban mobility and ultimately urban freedom.

Cities have shown tremendous resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic and will continue to drive change and innovation. Dediu insists that the micromobility boom seen during COVID times will have long-lasting impacts. Micromobility is indeed the only path to absorb the gigantic forecasted demand for individual mobility.

Car demand will keep growing, everywhere in the world but especially in Asia, and by 2035, based on current adoption curves, emissions of the individual transport sector might increase by 60%. An intolerable situation. We have no other choice than to push these future drivers towards micromobility solutions, in order to substantially reduce emissions.

The famous “twice with half”: we could have twice the number of drivers with half the amount of emissions thanks to micromobility.

In order to achieve this, we should not get distracted by autonomous vehicles, flying taxis or other quick technology fixes. Those are merely empty promises and we better first get our bike lanes done before moving to the next step.

Where are we heading?

As much as I like Dediu’s optimism and vision for the future of urban mobility, I feel that the situation on the ground is somewhat different. There are still some obstacles but they could all be overcome.

First, city authorities are often ill-equipped to think ahead about the deployment of innovative micromobility services. New solutions and products emerge very quickly and it’s difficult to catch up. The conflict between technologists and urbanists is at an all-time high here. Micromobility goes beyond just mobility objects but also raises concerns about inequality of access, deployment of safe and dedicated infrastructure, shared public and private sector responsibilities. An holistic approach is required to ensure micromobility truly delivers its benefits. 3 Ways Cities Can Leverage Micromobility Services for Good

Second, the current approach adopted by many cities is high regulation, with good reasons as personal mobility devices can become a threat for vulnerable pedestrians. Here is a good list of current regulations worldwide Micromobility Policy Atlas. Singapore, where I live, has developed a simple and effective framework, specifying which kind of micromobility device can go where. If pragmatic, this approach is somewhat reactive to the micromobility change. Shouldn’t we also discuss about the future of streets, education on new mobility behaviours, economic opportunities related to micromobility? The conversation is largely unfinished.

Third, we need to realize that micromobility will be one of the major drivers of change in urban design. This is something we already discuss in one of our post earlier this year Issue #3 Welcome to the Ghost Road - an exploration of our driverless future As micromobility continues to integrate itself into the urban landscape, planners and policy makers need to rethink street designs and ensure that streets become multimodal and safe for a fast-changing and fast-growing base of riders. Check out this playbook Parking & Street Design “One of the biggest challenges facing cities since the introduction of shared micromobility services is where these vehicles should operate as well as where they should be parked and stored when they’re not in use.” If you have any concrete examples or references, especially in Asia, please share them with me!

The micromobility revolution is just starting. Definitely a topic we will explore again in the newsletter.

📝 This week

The Dangerous Promise of the Self-Driving Cars In his new book, historian Peter Norton punctures the claims of autonomous vehicle companies and warns that technology can’t cure the urban problems that cars created.

Seville to become world’s first city to name and rank heat waves

People’s brains are not wired for optimal navigation. Cellphone data shows that people navigate by keeping their destinations in front of them – even when that’s not the most efficient route

High-speed railway construction boom from 1976 to 2019. Hello, China!

💡 And also

🎙 Speaking of China, don’t miss our latest podcast episode with Andrew Stokols, from MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, about China’s urban future 🇨🇳 We discuss why the future of urban China is more tortuous than ever: the return of the Central power, Xi Jinping's plans for a new emblematic city and the (chaotic) Belt and Road Initiative.

That’s it for today. As usual, a small 🧡 at the bottom of the article goes a long way !

Thanks for your support. This newsletter will take a mini-break and come back soon for a new podcast episode. Stay tuned.

Love the point you make about

"Micromobility goes beyond just mobility objects but also raises concerns about inequality of access, deployment of safe and dedicated infrastructure, shared public and private sector responsibilities."

Micromobility deployments done without coordination from other public/private actors is likely to fail, and even if successful, done in isolation it can miss out on reaching maximum benefits for all stakeholders.

Hello Fabien. I'm Joaquin. I read your Cities of mind with great interest. You write with clarity about issues that involve us all. A week ago we moved with my girlfriend to Hamburg, a new challenge. She works in foreign trade. We are Uruguayan. I am passionate about mobility and urban design. I would like to ask you where I can learn and train in these disciplines.

In the meantime I read and write.

Thank you very much for your time.

Regards

Joaquín