The Return of the Bicycle Kingdom(s) - Issue #14

On why Asian cities' love affair with bicycles needs to be revived.

Hello everyone!

In this week’s issue, we’ll follow-up on our latest article "Micromobility is urban mobility" - Issue #13 and explore the future of cycling in Asian cities 🚲

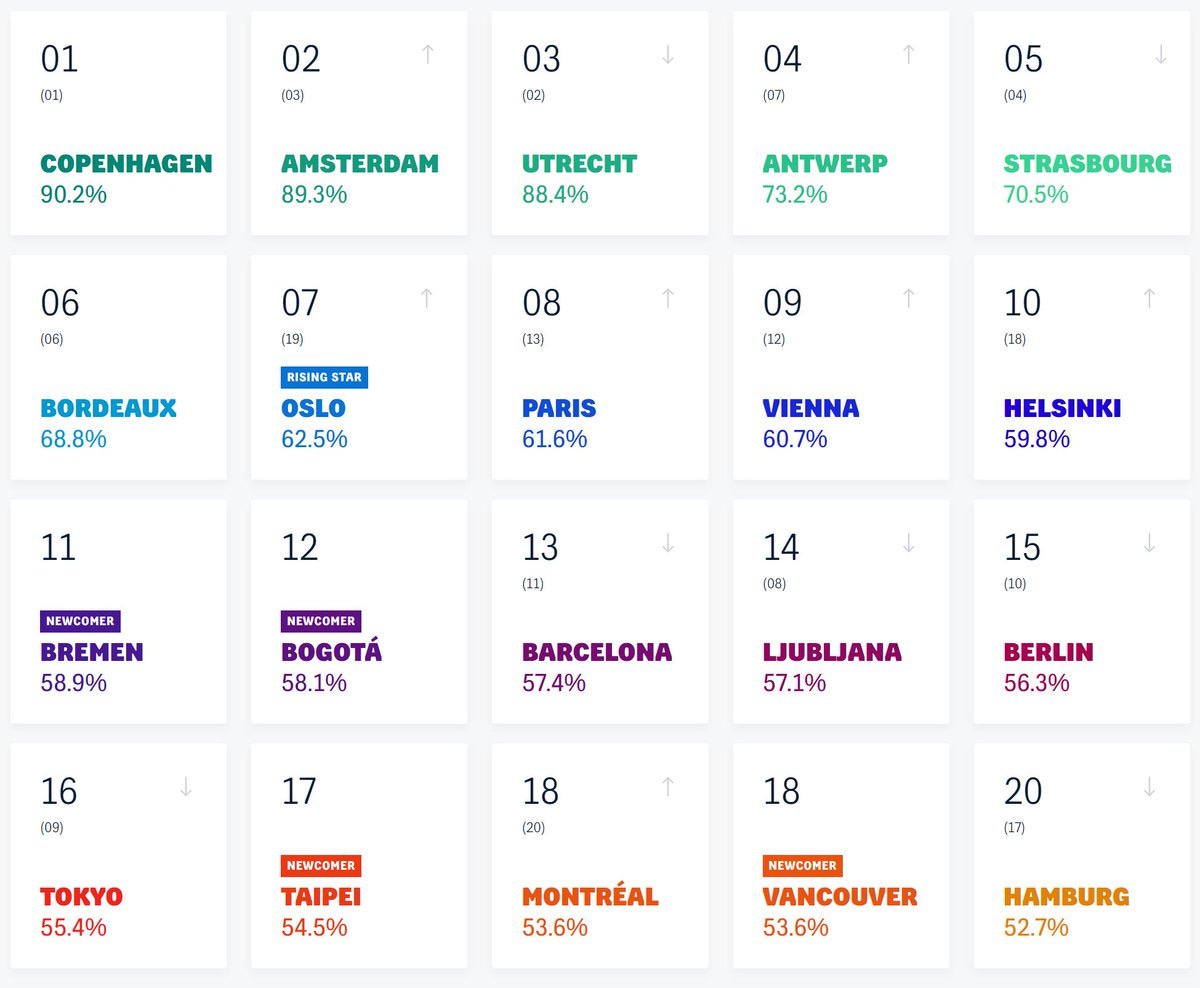

Although much ink has been spilled on the potentials of cycling to improve city life, I haven’t seen many articles dealing with the situation in Asia. The global conversation on cycling is still largely guided by European (and, to a lesser extent, American) cities. Maybe that’s because Asian cities don’t really stand out in terms of “cyclability” (in the 2019 Copenhagenize Index, a global ranking of cities according to their bicycle-friendliness, only 2 Asian cities make it to the top 20) or maybe that’s because Asia’s love story with bicycles has long been forgotten.

Let’s see why urban cycling still has a bright future in Asia, and not only in the city cores.

Before starting, let me say that my interest in cycling, micromobility solutions and low-car urban design approaches has hugely increased since my read of Melissa & Chris Bruntlett’s latest book Curbing Traffic: The Human Case for Fewer Cars in Our Lives.

The Bruntletts’ book is a formidable account of what it’s like to live in a cycling paradise (in that case, the city of Delft in the Netherlands) and all the benefits that come with living in a low-car urban environment, from individual empowerment, gender balance, social interactions, noise reduction, inclusiveness, economic development, public health, resilience and so forth.

Despite all the focus on cycling right now, micromobility solutions are quite absent from COP26, currently held in Glasgow, where 200 countries are discussing their ambitions towards mitigating climate change. And that’s a real bummer, considering all the benefits cycling and micromobility could trigger. But that’s a different debate.

Urbanization killed the bicycle star

Once upon a time, cycling was the most natural mode of transportation in Asian cities. And the story starts in China.

When the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949, it embraced the bicycle as a symbol of economic progress. The creation of national brand champions, such as the iconic Flying Pigeon, founded in the city of Tianjin in 1950, led to a fast adoption of cycling in Chinese cities.

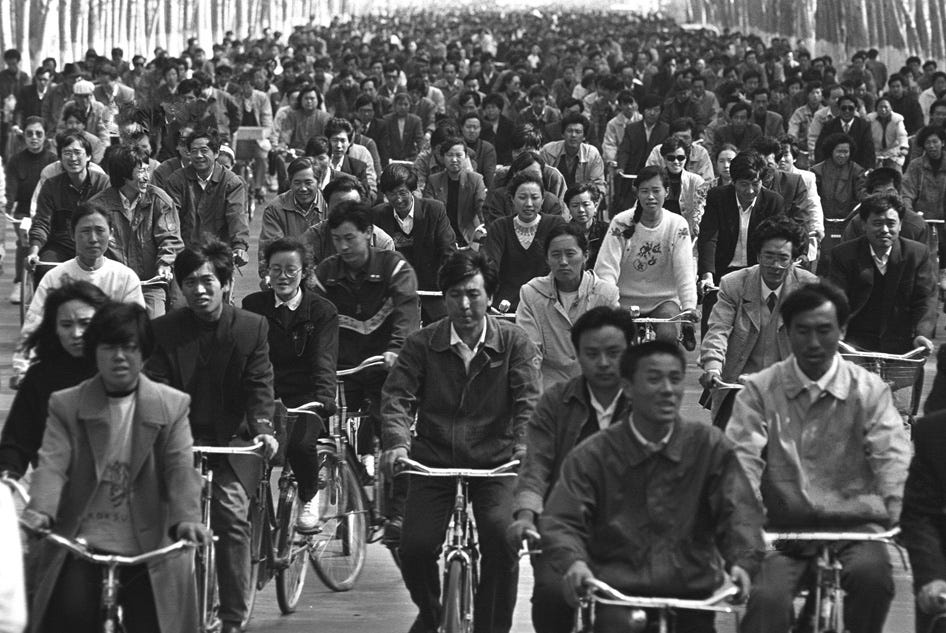

While the expression was coined during the Mao era, China became widely known as the “kingdom of bicycles” in the 1980s. Hordes of bicycles were filling the roads of Beijing, leaving deep impressions on visitors from the West who came to witness China’s economic opening.

Bicycles dominated the streets of fast-growing Chinese cities in the 1980s and 1990s. Public transport was quite limited and cars were rare and unaffordable, so bicycles were basically the essential vehicle for urban travellers.

“ Starting in the Mao era, urban planners had deliberately built roads that accommodated “bicycle mass transit systems” with 3-lane roadways that featured dedicated bike paths. Beijing, an especially bike-friendly city, had 76% of its road space taken by cyclists in 1988, including busy intersections that saw 20,000 bicycles an hour. By 1995, the city had 8.31 million bicycles on its roads” as described in this excellent recount The Rise, Fall, and Restoration of the Kingdom of Bicycles

Figures that will make other bike-friendly cities pale in comparison.

Unfortunately, pedal power started to decline in the mid 1990s. That’s when China’s urbanization greatly accelerated, leading to a soar in car adoption. Urbanization in China saw cities sprawling, generating lengthier commutes and a need for long-distance transport such as cars, subways and trains. This shift towards cars transformed urban living, affecting everything from energy demand, air pollution, infrastructure development and traffic congestion.

Cars also became the new symbol of urban modernity, a familiar story across developing countries. As people make more money, they start to buy cars which become a proxy for social status. Bicycles come to be seen as “for the poor”.

This scenario repeated itself across Asia. Cycling also used to be the main mode of transportation in Singapore.

“In 1960, there were 268,000 registered bicycles compared to 63,000 cars and 19,000 motorcycles in Singapore. Several major roads had cycling tracks next to footways. But, as incomes increased in the 1970s, these trends reversed: car and motorcycle ownership soared, while cycling came to be viewed as an inferior form of transport.”

Reflecting this shift in commuting preference, transport planners in Singapore focused their efforts on building a comprehensive and modern road network for motor vehicles and removed earlier cycling tracks to make way for wider roads.

The bumpy restoration of cycling

The first decade of the 2000s brought greater awareness about the dramatic impacts of car dependence. The negative side effects were quite obvious: traffic congestion, road accidents, oil dependence, air pollution.. The idea of restoring cycling to tackle mobility challenges across urban Asia emerged.

In China, the central government started to rethink the auto-centric urban development path that the country had pursued since the 1990s. Cities began to restrict car use and in 2012, the central government started to encourage “slow-moving transportation”, through new “Guidelines for the Planning and Design of Urban Walking and Bicycle Transportation,” pushing forward standards for urban cycling.

Hangzhou was one of the first Chinese cities to introduce a bike-sharing system in 2008, following a trend that saw many cities adopting similar schemes, based on docked bikes, smart-card technologies, automated check-in and check-out and a tracking system for the operator to manage load balancing. Hangzhou still boasts the largest docked bike fleet in the world, comprised of 86,000 bikes and accounting for 473,000 daily rides (in comparison, Paris’ Velib, Europe’s largest scheme, has around 20,000 bikes and around 200,000 daily rides).

Despite these successful preliminary steps, cycling in Chinese cities was deemed too inconvenient for urban trips.

As China rapidly adopted smartphones and mobile apps over the 2010s, some entrepreneurs saw opportunities to monetize more efficiently bike-sharing. Startups such as Ofo launched in Beijing in 2014 and MoBike in Shanghai in 2015 with a new kind of service: dockless bikes that could be unlocked via your smartphone and dropped almost anywhere. Free-floating bikes addressed the last-mile problem of millions of people whose work or home was not walking distance from subways or other modes of transportation. Startup companies literally flooded Chinese cities and other urban areas in Asia and Europe with colourful dockless bikes.

And you know how the story went.. The dockless bike-sharing bubble burst as quickly as it inflated. Bike-sharing startups which were waging a “subsidy war”, in order to win market shares and crush rivals, had to take enormous losses on heavily-discounted user fees. A completely unsustainable business model. In addition, dockless systems still needed to be load balanced and faced a lot of backlash due to vandalism and unregulated use of public space, such as sidewalks. As a result, many startups went bankrupt, leaving in their wake huge “bicycle graveyards” (whose photographs have travelled the world) that haunted Chinese cities for a while.

This episode shed some light on the limits of bike-sharing systems. Even if they are a good indicator of a city’s commitment to improve urban cycling, they are not a panacea and can have cascading negative effects if not properly managed.

The bike-sharing story in China is not over. Close cooperation between operators and regulators have helped establish more mature, stable bike-sharing companies, all backed by giant technology companies. Geofencing is also now widely used to avoid chaotic bike parking on sidewalks or public spaces.

Today, there are 3 major platforms in China: Meituan (e-shopping and delivery giant which bought MoBike in 2018), Helloglobal (backed by Ant Group, affiliate company of Alibaba) and DiDi Bike (China’s ride-hailing giant which bought Ofo in 2018). Despite concerns about the profitability of these schemes, the dream of dockless bike-sharing is still very much alive in China.

City authorities have also started to enforce strong legislations to cap the number of shared bikes. In 2021, the city of Beijing decided to cap shared bikes at 800,000 in urban districts, down from 844,000 today, to deal with the city’s surplus, improve user experience and general tidiness of the urban environment. Beijing is also asking operators to expand their services to suburban areas.

Outside of China, only a handful of Asian cities stand out in regards to their cycling policy.

Tokyo is the 1st Asian city ranked in the 2019 Copenhagenize index of bicycle-friendly cities. Tokyo has been a city of cyclists for many years but not because of the official planning narrative, but rather because of its people. In the world’s largest city, millions of people bike on a daily basis, using their iconic Mamachari to ferry goods, children, and themselves to the store, school, or train stations. Tokyo boasts a strong cycling culture but it does not translate well into the built environment, with very few dedicated cycling lanes. Cycling is very much a suburban thing in Tokyo, with 18% of all commuting passengers arriving at their local train station by bike.

In Taipei, Taiwan, cycling really picked up momentum in the last decade, following the launch of the YouBike docked bike-share scheme in 2009, one of Asia’s most successful bike-sharing system outside of mainland China. Offered by the Taipei City Department of Transportation in collaboration with local manufacturer Giant Bicycles (which also happens to be the world’s largest bicycle manufacturer), YouBike is expanding in 2021 with the aim to transport more people (today, the scheme boasts 13,000 bicycles and around 83,000 daily rides).

Singapore has also improved a lot regarding cycling. Despite its hot and humid environment, Singapore is pushing forward its cycling infrastructure, with the objective to have 1,320km of cycling paths and park connectors by 2030 - nearly trebling today’s network length. Dockless bike-sharing systems are down to only two players today, SG Bike and Anywheel, vs nine back in 2017 during the bike-sharing craze.

Biking beyond the urban core

The COVID-19 pandemic has renewed interest in cycling in Asian cities, with people becoming more aware of the health and environmental benefits of cycling.

But what can cycling do to support suburban mobility in sprawling Asian cities?

Worldwide, the mobility gap between the core and the periphery is widening because of the pandemic: new bike lanes popping up in city centres mean that those living in gentrified urban cores enjoy enhanced mobility choices.

“Many of the most vocal cycling advocates live in gentrified urban cores. Measurable rates of cycling — such as journey-to-work — are far higher in these areas.”

“To address these imbalances, the goal should be to develop a comprehensive network cycling infrastructure across the city. Bike lanes should be a ubiquitous piece of infrastructure found downtown and in the suburbs, in rich neighbourhoods and poor ones. This is common in Dutch cities, where some of the best infrastructure can be found at the edges of cities.”

Despite the fact that they are sprawling, Asian cities still exhibit high-density residential land-use patterns in their suburban developments, which make them conducive to cycling. Cycling infrastructure innovation mostly takes place outside of the urban core.

In Singapore, the best cycling infrastructure is to be found in the “heartlands”, self-contained towns that are being stitched together through cycling-friendly park connectors.

In China, cycling innovation happens in secondary cities. Danish office Dissing + Weitling Architecture completed in 2017 an 8km-long elevated cycling path in the city of Xiamen (4.29 million inhabitants). The Xiamen Bicycle Skyway, which the architects claim is the longest of its kind in the world, covers five major residential areas and three business centres in Xiamen, using space below the elevated roads of Xiamen’s Bus Rapid Transit.

Bicycle skyways are not the only way forward and there is a risk that cities focus too much on them rather than on “capillary bike lanes” that provide access to communities and businesses (it is often on secondary lanes that a lack of space, road rights and poor occupation strategy create chokepoints for bicycles, putting people off from cycling).

But those examples are a good testimony of Asian cities’s readiness to accelerate their cycling efforts and drive the demand for micromobility. Taken together, these trends may well restore some of the territory lost by the kingdom of bicycles.

Asia has key assets to outperform other cities in promoting cycling, from urban density, business ideas, technology readiness, investments in infrastructure to regulatory sandboxes. Time to move faster!

📝 This week (100 % mobility)

Austria’s $3.50 go-anywhere ticket to fight climate change The annual pass offers access to all public transport nationwide for just $3.50 a day.

Cars Are Going Electric. What Happens to the Used Batteries?

Boston’s newly elected mayor Michelle Wu has a plan for her city and that involves transit, walking and cycling Michelle Wu Can Be America’s First Actual Honest-to-Goodness Climate Mayor

Not to be missed: a deep dive into the urban gig economy “The common issues that gig workers face, whether in Manhattan or Mumbai, Johannesburg or London, is spurring the creation of a truly global movement, as drivers and riders link up across borders, pressuring companies and governments to recognize one simple fact: Gig work is work, and it needs to be paid as such.”

That’s it for today. As usual, a small 🧡 at the bottom of the article goes a long way !

If you wish to stay up-to-date with Cities in Mind, please follow us on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Thanks for your support. See you next Wednesday.

Great article, really enjoyed hearing in particular China's historical relationship with the bicycle, I had no idea they were 76% of roadspace in 1988. Probably unfeasible to get back to such a high number ever again but encouraging see Asian cities picking up more and more cycling infrastructure and (properly managed) bikeshares. When I lived in Taipei I used YouBike all the time, it was a great system especially on the larger roads where they had dedicated, curb-separated bike lanes.